The Odd Duck

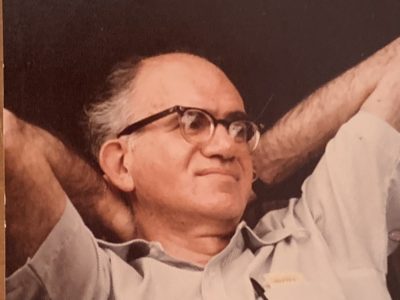

Odd duck. It’s such a strange, old-fashioned way to portray a person, but I’ve never found a better term to describe my father.

Stanley Wallace always stood out from the flock. A lifelong Brooklynite, he sounded like an English professor, never using the wonderfully clamorous accent that made his borough famous. He was a lifelong baseball fan, but unlike the hordes of Dodgers fans around him, he rooted for their archrival New York Giants. (And, later, for the Mets, which did reunite him with the rest of his borough.)

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, when any sort of activism on racial or political issues could get you into deep trouble, he was a believer in social justice. Even though he graduated from Duke University at age 19 at the top of his class, his modest outreach—such as attending interfaith services and planning sessions in Black churches—nearly destroyed his chances of getting into medical school. (He was finally admitted to the 34th school he applied to, opening the doors to a celebrated, deeply fulfilling career as a rheumatologist, researcher, and educator.)

Dad stood out in another way, too: Decades before the environmental movement blossomed in the 1960s, he was an ardent environmentalist, enthusiastic amateur naturalist, and list-keeping birder. (Though of course it was called “bird-watching” back then.)

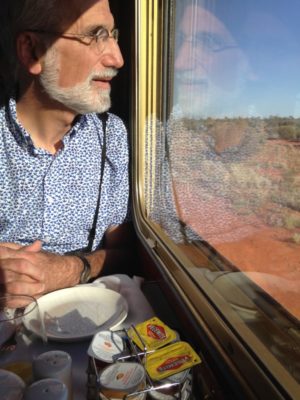

I grew up to share my father’s refusal to march to anyone else’s drum, his beliefs in social justice, and (alas) his devotion to the Mets. But perhaps the passion that lives on most strongly in me is his unwavering love of the natural world, his desire to see it preserved, and his enthusiasm for what inhabits it.

Especially the birds.

Among the vast array of species out there, Dad’s favorites were those found near water: the herons, egrets, and other wading birds, followed closely by the sandpipers, plovers, and other shorebirds. These may seem like still more iconoclastic choices (waterbirds for a man who lived in Midwood?), but Dad’s vision always stretched far beyond his urban backyard. Starting in the early 1940s, when both national enthusiasm for nature and access to the waters surrounding New York City were at a low, he found Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, hard by Idlewild (later Kennedy) Airport in Queens.

Jamaica Bay, which comprises 12,600 acres of open water, salt marshes, brackish ponds, and woodlands, came under the auspices of the National Park Service in 1972 as part of the Gateway National Recreation Area. But when Dad started visiting it—and when he first brought me there two decades later—this unique spot was managed as a park and preserve by New York City.

In virtually every season, Jamaica Bay provided me (and, at various times, my two brothers) with an early education in the ebb and flow of bird life throughout the seasons. Even with its smoggy air, views of distant city buildings, and the occasional roar of jets coming in low to the airport, it felt like a visit to an older, purer world than the one we usually inhabited.

In spring and summer, the salt marshes and edges of the large, freshwater West Pond were dotted with birds you could hardly believe would even visit the big city. Great and Little Blue Herons and Snowy and Great Egrets would stalk the shallows, while American Coots and various ducks would paddle in the deeper areas.

The refuge was also home to the fascinatingly prehistoric Glossy Ibis, which to Dad and me truly represented the magic and mystery of birds. Even now, decades later, I’ve only seen this odd species, with its dark, iridescent plumage and scimitar-like beak, in a few other places. It will always represent Jamaica Bay to me.

The last stretch of the trail around the West Pond took visitors away from the water and through some woods. Dad and I always enjoyed this change of pace, which gave us the chance to glimpse colorful songbirds like Baltimore Orioles and Scarlet Tanagers, and—on peak spring-migration days—flitting little things like warblers and vireos. Jamaica Bay awoke in me a lifelong love of these tiny avian gems, though to Dad they simply moved too fast and hid too well to be much fun.

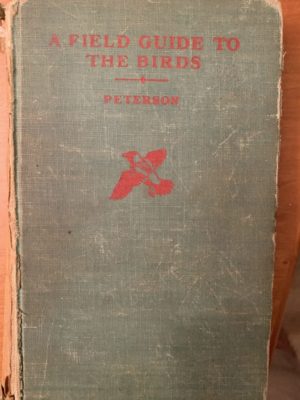

Our last stop was usually at the wilder East Pond, a haven for shorebirds in summer and fall. I always enjoyed seeing the Yellowlegs, Willets, and other larger species (and still do!) we spotted there. But Dad had a special affection for the little, hard-to-identify sandpiper species collectively known as “peeps,” which would always spur him to pull out his trusty Peterson’s Field Guide to the Birds. (He carried—and I inherited—a 1947 edition of that visionary forerunner to all other field guides.)

I rarely saw Dad happier than when we were carefully studying a bird, knowing that eventually we’d reach that “aha!” moment and give a name to the one we were looking at. I think the process must have appealed to the research scientist in him, as it appeals to the writer, amateur naturalist, and birder in me.

After our visit to the East Pond, we’d head home, a transition that always came as a shock to me. Within ten minutes we’d have left the wilds behind for the endless commercial strip that was Cross Bay Boulevard. Not that civilization didn’t have its benefits: We’d always stop for lunch at Buddy’s, a huge, noisy restaurant where we both enjoyed the hot dogs and I got to play the pinball machines.

But I always felt a sense of loss, of being thrown out of paradise, as we left Jamaica Bay behind, and I know Dad felt it too. I think it was that feeling, of something precious lost, that most spurred my lifelong love for nature, my drive to do whatever I can to help preserve what’s left, and my unquenchable yen to visit places as familiar as Croton Point Park and as exotic as the Serengeti Plains or the Great Barrier Reef. It’s not just wanderlust, but something deeper and more essential: the desire to recapture the wonder I felt back then, every time I saw my first ibis of the spring.

Stanley Wallace passed away in 1989, a dedicated physician, educator, conservationist, and birder to the last. Today I want to say Happy Father’s Day, Dad. Thank you for showing me Jamaica Bay, and for being the odd duck you were.

Copyright © 2021

by Joseph Wallace