The Mockingbird’s Meaning

“Mockingbirds don’t do one thing but make music for us to enjoy. They don’t eat up people’s gardens, don’t nest in corn cribs. They don’t do one thing but sing their hearts out for us. That’s why it’s a sin to kill a mockingbird.”

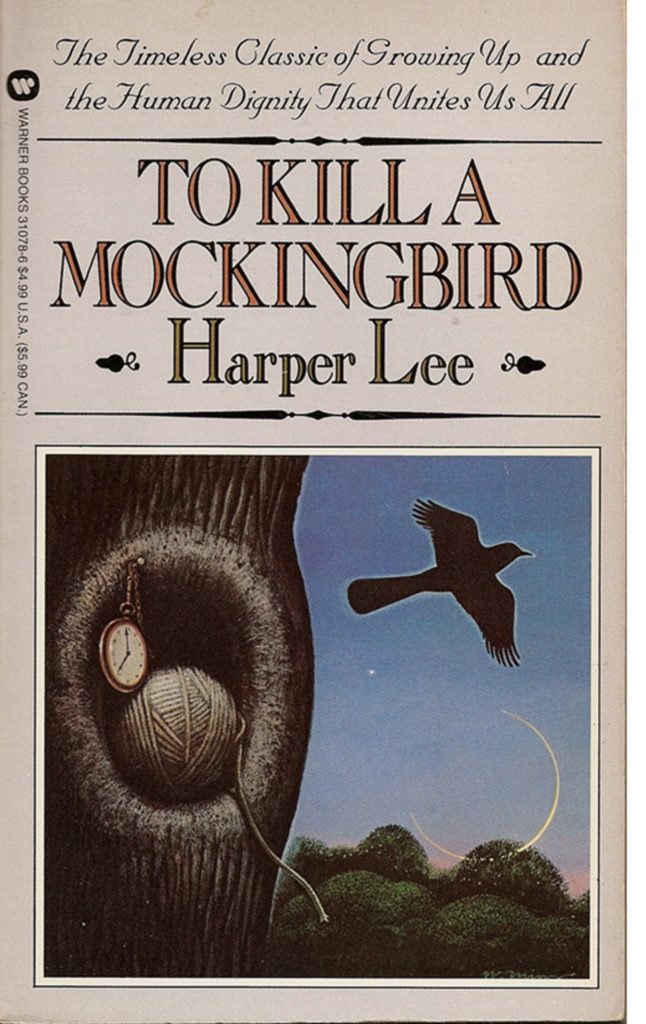

This is perhaps the most famous quote from Harper Lee’s beloved To Kill a Mockingbird. It’s a novel I love, yet from my very first encounter with it as a child, I knew that Lee hadn’t gotten Northern Mockingbirds quite right.

She’d made them sound like some sweet, limpid caroler, a North American nightingale, perhaps. Having been dive-bombed by angry mockers when I approached too close to their (hidden) nest, and woken more than once in the middle of the night by their loud calls, I had a different opinion.

In some ways, I still do. Northern Mockingbirds have always been one of my favorite species because they’re not sweet and limpid. And, as we all know, they don’t carol.

Quite the reverse: Mockers are conspicuous (“rain-cloud gray with bursts of white,” as nature writer Gordon Grice describes them), tough and brassy. The males are fiercely territorial, often engaging in violent battles with potential rivals, and they’re equally fearless in confronting anything that might hunt them or raid their nests.

In his book The Red Hourglass: Lives of the Predators, Gordon Grice tells of a rattlesnake that made the mistake of passing beneath a mockingbird nest, provoking a series of attacks. The bird targeted the snake’s head and eyes, leaving it mortally wounded. Mockingbirds have been known, Grice says, “to keep after a rattlesnake for an hour. They don’t relent even when the snake leaves their territory; they follow and perform an execution.”

Their flashy looks and personalities make mockingbirds one of the most noticeable species in any habitat where they appear. (In this season, there appears to be a new mockingbird territory every thirty feet at Croton Landing.) They seem to demand our attention, often sitting in plain sight on a bare branch or fence top, fixing you with a dark eye as they watch you pass by.

But if they’re usually easy to observe, it’s their song that makes them famous. Of course, it’s not quite a “song,” but mockers’ talent for mimicry that gives them their common name.

Mockingbirds have the ability to imitate the calls of dozens of other bird species. (And not just birds. They’re also good at car alarms and other human-created sounds.) Stop to listen to one perform, and you’re quite likely to hear its take on robins, cardinals, wrens, orioles, and blackbirds, among others.

They do have their own songs, too, whistled phrases that are similar in tone to their mimicked calls. But the vast majority of the birds’ calls are imitations.

So we know a fair bit about mockingbirds. But it turns out there’s also a whole lot we don’t know. In fact, much about the species remains wreathed in mystery.

For example, scientific consensus has long held that mockingbirds learn new songs throughout their lives. Yet when biologist Dave Gammon, a professor at Elon University in North Carolina, tested that theory by repeatedly playing songs of new species for local mockers, he found that they didn’t learn a thing.

Gammon then studied the songs of individual mockingbirds recorded over several years, again finding that the birds’ overall repertoires never changed. So it appears they—like many species—may learn all they need to know as youngsters.

Most young birds learn to sing by listening to their parents. But no one seems to know whether mockers learn from their parents, by listening to other birds, or both. Which leads to another question: If the imitations are handed down through generations, then who was that bird who first added other species’ songs to the repertoire? And why?

Why remains the biggest mystery of all. What advantage does a mockingbird gain by learning dozens of other birds’ calls? In most bird species, males sing as a way of attracting females; strong songs, like larger size and brighter colors, show health and strength. But do female mockingbirds (who sing as well) choose the male with the loudest voice? The one with the most diverse repertoire? No one knows for sure.

I think this is fascinating: We actually understand little about a bird we think we know so well, which has appeared so often in our creative consciousness. Harper Lee is far from the only author to have been inspired by the mockingbird; much more recently, Suzanne Collins named her Hunger Games novel Mockingjay, after a jay-mockingbird hybrid.

Songwriters have turned to the mockingbird even more often. The traditional lullaby “Mockingbird” (“Hush little baby, don’t say a word, Mama’s gonna buy you a mockingbird) is perhaps the most famous, especially since it was transformed (by Inez and Charlie Foxx) into an R&B version covered by everyone from Dusty Springfield to Aretha Franklin and Ray Johnson to James Taylor and Carly Simon.

There’s also Patti Page singing “Mockin’ Bird Hill” (“It gives me a thrill to wake up in the morning to the mockingbird’s trill”) and, recently, singer-songwriter Lindsay Lou’s evocative “Southland” (“Come on, little mockingbird, sing us a song”), among others.

This persistence in our nation’s art has made me understand something new about the meaning of mockingbirds. Far more than just appealing splashes of color and noise around us, they conjure up still, hot summer days, childhood, the peacefulness of less complicated times. They’re also a gateway to the natural world, to a place that can restore us…but that we don’t always remember to slow down and notice.

I’m thinking that I’ve been getting it wrong, and that Harper Lee had it right all along.

Copyright © 2020 by Joseph Wallace