The Eagle’s Lesson

I spotted six Bald Eagles during a walk in Croton Point Park last week: Two riding ice floes out in the Hudson River, three adults scattered around the park, and a perched immature that—for a few exciting moments—I thought might even be a rare Golden Eagle.

Six Bald Eagles in a single morning at that park is a lot, but not a lot. In this season, it’s a rare visit that doesn’t turn up at least one or two. (My wife and I once counted 17 in a single day!)

In fact, Bald Eagles have become so much part of our regular lives around here—and nearly everywhere in the North America where there’s plenty of water and fish nearby—that we almost expect to see them. Despite their grandeur, we may even begin to take them for granted.

It wasn’t always this way. In fact, twenty years ago Bald Eagles were a rare sight, and not that much further back they were on the brink of disappearing entirely. Even though the species is thriving now, I think we need to keep the story of the eagle’s brush with extinction vivid in our minds. As we head into an increasingly perilous future for our wildlife and ourselves alike, it still has important things to teach us.

Oddly for a bird chosen (in 1782) as the national symbol, the Bald Eagle was viewed with suspicion, if not loathing, by European colonists as soon as they arrived on the continent. (Many Native American tribes, on the other hand, revered the bird. Except for a small number of eagles killed for their feathers, which were used in ceremonies, the birds and their nesting sites were strictly protected.)

Despite eating mainly fish, eagles—along with wolves, coyotes, mountain lions, Golden Eagles, and a variety of smaller predators—were slaughtered for killing livestock. Not that an accurate understanding of the bird’s diet protected it: In coastal communities it was wrongly blamed for harming commercial and sport fisheries, and slaughtered for that, too.

The Bald Eagle’s reputation was so bad that Alaska actually paid a bounty for every eagle carcass turned in between 1917 and 1959. Why did state officials finally rescind the reward? Not because of environmental enlightenment, but because Alaska was about to become the 49th state. Someone realized that paying residents to kill the symbol of the nation you were about to join wasn’t a good look.

As if this sort of persecution wasn’t enough, a slew of other factors also helped send the Bald Eagle hurtling towards extinction. One was habitat destruction. It’s hard to imagine now, but much of the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, and other regions were virtually clear-cut by the early 19th century, as native woodlands were converted to farmland. Bald Eagles, deprived of their nesting grounds, were among the many species driven away by this deforestation. (Even deer were rare in the Northeast in those days!)

Then there was the rise of industrialization throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, and the water pollution that progress inevitably brings. Every new mill and factory, every mile of waterside railroad track laid, led to increasingly tainted lakes and rivers. Over the course of decades, that meant fewer fish, less food, and ever-declining eagle populations.

And, of course, there was the mushrooming human population’s insatiable need for food, including seafood. Salmon and trout in the rivers, Atlantic Menhaden and many other species in coastal waters—as these fisheries declined, then crashed by the early 20th century, the Bald Eagle was left without the prey it had evolved over eons to hunt.

All of these factors were dire enough on their own. But what truly sent the Bald Eagle (and such other topline predators as Golden Eagles, Ospreys, and Brown Pelicans) to the precipice were pesticides, especially the notorious DDT.

DDT’s story is a frighteningly familiar one, but it bears retelling. Like other pesticides, it wasn’t meant to harm birds, merely to help keep crops “healthy.” What this supposed “do no harm” approach resolutely ignored (despite urgent warnings from Rachel Carson and other early environmentalists) was one simple fact: DDT and other pesticides didn’t stay where you sprayed them, or affect only the species you meant to kill.

The message finally got through when Carson’s groundbreaking book Silent Spring was published in 1962. At last the public understood that DDT sprayed on fields ended up in soil, lakes, rivers, and—most devastatingly of all—in animals, where it remained and accumulated. Every time a Bald Eagle ate a fish, it would get walloped by a far larger amount of DDT than even the pesticide’s creators had ever imagined.

The cumulative impact of DDT poisoning on Bald Eagles was devastating. Along with sickening the eagles, it interfered with the birds’ ability to process calcium, causing the females to lay eggs with thin shells. Eagles following the age-old practice of sitting on their eggs would rise to find only a crushed mess remaining.

The most efficient way to destroy a species is to prevent it from breeding successfully. Even long-lived birds like eagles, which can survive for 20 years in the wild, aren’t fertile forever. Once you’ve knocked out an entire generation’s ability to raise its young, where is the next generation going to come from?

And that’s what nearly happened because of DDT and other factors. By 1963, there were a mere 417 nesting pairs of Bald Eagles across the entire lower 48 states. Like such extinct species as the Passenger Pigeon and the Carolina Parakeet, the eagle and many other species nearly vanished without anyone noticing until too late.

Thanks to Rachel Carson and a burgeoning environmentalist movement, that didn’t happen this time. Once DDT’s effects on eagles, pelicans, and other species became common knowledge, the public’s outcry was loud and immediate. In the face of a cascade of bad publicity, the government responded forcefully. DDT was banned across the U.S. in 1972, and in 1973 the Bald Eagle was one of the first birds placed on the strong, new Endangered Species Act (ESA).

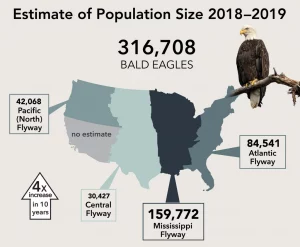

The eagle’s response to this reprieve was slow at first, but over the years its population rebound has accelerated to resemble a freight train. As of 2020, scientists put the overall eagle population in the Lower 48 at an astonishing 316,700 birds, including more than 71,000 nesting pairs. (Saying that you spotted six eagles on a morning’s walk sounds a little less impressive when you realize that you’ve seen just .000019% of the bird’s population.)

All in all, the Bald Eagle represents one of the greatest environmental success stories of the 20th century. And its success, along with that of pelicans, Ospreys, and other DDT-afflicted birds, is worth celebrating. It proves that through smarts, dedication, hard work, and raised voices, we humans can make a positive difference in the world around us…and even reverse the grievous mistakes we make along the way.

But that’s just part of the eagle’s lesson. Its story also teaches us that, in a world beset by environmental threats large and small, we’re going to need all our smarts and dedication, every bit of hard work we can spare, and ever-louder voices. That’s the only way we’re going to keep the next Bald Eagle—or even this one—thriving through the rest of this century and beyond.

by Joseph Wallace

Copyright © 2022

PS to learn more about Bald Eagles and other raptors in the Hudson Valley, join in on Teatown’s EagleFest coming up the first weekend in February! EagleFest includes both online and outside events: www.teatown.org/events/eaglefest/