The Sentinel Butcher is Watching

As I stood alone in the trailhead parking lot in a remote corner of New York’s Fahnestock State Park on a bleak December day, I confess that I felt a little foolish. And I had reason to: I’d just made an hour’s drive—on a workday, no less—in search of one bird amid the vast expanse of fields and woods that surrounded me.

Just to be clear: I’m not talking about one bird species, but one single, solitary individual. And a pretty small one, too, about the size of a robin.

This kind of quest makes even an avid birder like me start to question his life choices. There were so many other, more productive things I could have been doing with my time. Writing. Seeing friends. Vacuuming the house.

But this, I’d told myself, was a bird worth breaking the rules for. It was a Northern Shrike, a rare winter visitor to the Northeast that had shown up in the area a few days earlier, and I’d never seen one.

Shrikes are among the coolest birds around. For their size and weight (the Northern measures just nine inches from head to the end of its tail and weighs about two ounces), they may be the fiercest predators on the planet, tiny but worthy descendants of the carnivorous dinosaurs that once dominated life on earth.

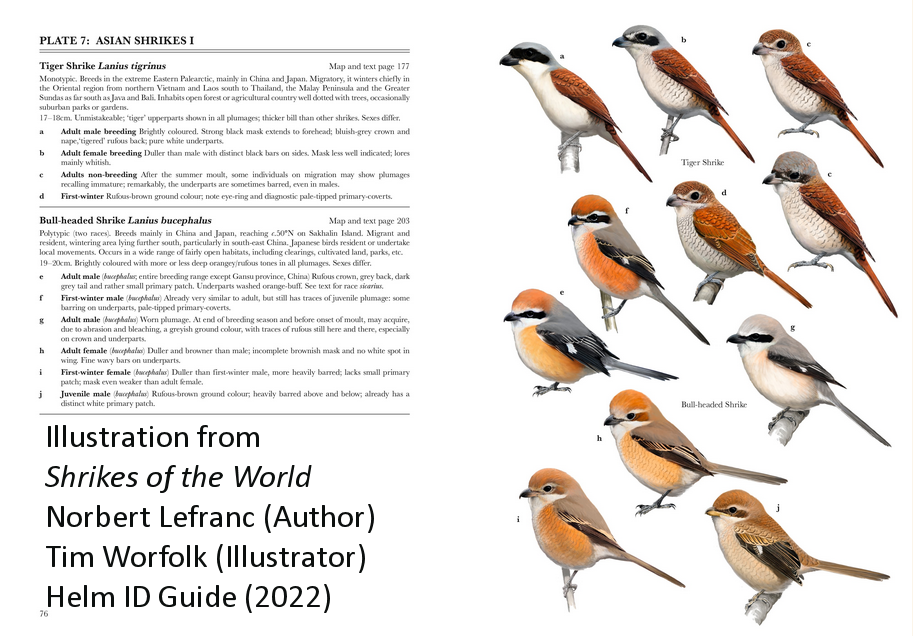

The 34 shrike species are found mostly in Eurasia and Africa, with only the Northern and its close cousin the Loggerhead living in North America. Wherever they’re found, though, shrikes are ferocious hunters who employ clever and creative methods not seen anywhere else in the bird world.

Shrikes’ unusual habits are even reflected in their Latin names. Both the family’s name (Laniidae) and the most dominant genus (Lanius) translate as “Sentinel,” marking the birds’ preference for perching at the tops of trees or bushes as they scan the surroundings for potential prey. And one Old World species—the Great Gray Shrike—has been named Lanius excubitor, which means “Sentinel Butcher.” It’s a vivid name that could be shared by many species, since it captures both the family’s patience and its ferocity so well.

It would be logical to expect birds the size of shrikes to “butcher” butterflies, crickets, and other small insects, but shrikes defy logic. Far from relying on mild-mannered little bugs for their diet, they attack and conquer larger creatures—including mice, voles, lizards, snakes, and larger birds—that can fight back with teeth, claws, and beaks.

Shrikes use a mix of stealth, craftiness, and a sentinel’s patience to take on such impressive prey. They are known to perch near well-used animal trails, waiting for the perfect moment to swoop down on an unsuspecting target. They’ll also hide near a larger bird’s nest, studying the parent birds’ habits. Having learned when the adults will be absent, a shrike can raid the nest and carry off a nestling without any fuss.

Shrikes also rely on a remarkable assortment of hunting techniques. For example, while they’ll use their beaks to snatch harmless insects, they’ll grab larger prey—such as a mouse—with their feet.

Shrikes don’t possess the powerful talons of hawks and eagles, which alone can disable a smaller creature. Instead, as a shrike grabs a mouse, it will bite down on the mammal’s spine just behind the head, causing immediate partial paralysis. (Flat, tooth-like projections on the shrike’s upper bill and corresponding indentations on the lower one act almost like tiny nutcrackers.) Then, once the mouse is paralyzed, the shrike will deliver the coup de grace, breaking its spine with a few ferocious shakes.

Having dispatched its prey, the shrike is confronted by a new problem. A whole mouse or vole is far too large to eat in a single sitting, but just leaving most of it behind would be wasteful. What to do?

The answer has made shrikes famous even among those with just a casual interest in birds. Northern Shrikes and other species will impale their recently deceased prey on a convenient thorn or barbed-wire fence. There the body remains, close at hand whenever the bird is feeling peckish. (This habit of hanging and “aging” their meat gives a new dimension to the birds’ reputation as butchers.)

That day in Fahnestock, I spent fifteen or twenty fruitless minutes wandering around, growing cold in the dimming afternoon light and feeling more and more foolish. Even vacuuming the carpets was beginning to sound appealing.

But then, just as I was about to give up, I spotted a tiny dark silhouette perched at the very top of a distant bare tree. Right away, I could tell by its posture, hooked beak, and black mask that it wasn’t a mockingbird, which can look quite similar at a glance. I’d finally seen my first-ever Northern Shrike.

It wasn’t, I had to admit, the most satisfying look, but it seemed like the best I was going to get. Yet again, though, my luck changed: As I began to turn away, the shrike decided it wanted to get a better look at me.

It flew to a closer tree, and then a closer one yet, and finally to the top of a tall bush no more than twenty feet from where I stood. From this vantage point, it stared at me with such focus and intensity that my jubilation faded, replaced by an unmistakable quiver of unease. Facing that unblinking gaze, I understood what it must feel like to have your measure taken by a creature that knows it is stronger, smarter, and better adapted than you are.

I stayed for several more minutes, but the unsettled feeling didn’t wane. And when I finally left, I found myself looking back over my shoulder once, then again. Each time, I saw that the shrike’s eyes were still following my every move. I felt very obvious, and very much alone, in that bleak landscape. Only when I was back in my car did the shrike fly back to the top of the distant tree.

Driving home, I felt the strangest mix of emotions, a combination of satisfaction and excitement and shakiness. Emotions that come back to me even now, as I write this.

Copyright © 2023 by Joseph Wallace