It’s a Bird’s Life: The Ruby-Throat

April and May in our region—and throughout the world’s temperate climes—is a riot of color. The varied greens of newly emerging leaves, the rainbow of blooming flowers…and the arrival of vividly hued migrating birds. Around here, warblers, orioles, tanagers, and others add ever-changing splashes of yellow, orange, crimson, blue, and green to the landscape.

By June, though, many of those species will have headed north towards their nesting grounds. What sticks around all summer from the vast flood of migrants are the American Robins, Gray Catbirds, House Wrens, Eastern Bluebirds, and others that stay to raise their young in our region. Over the course of the summer, we find their nests, hear their babies begging for food, spot their ragged, tailless, newly fledged young hopping around on our lawns. And we begin, quite naturally, to think of them as “our” birds.

But are they really ours? After all, most of our nesting migratory birds don’t arrive till May, and many start heading south again in September. The Northeastern U.S. is their home for only about four months, which means that they live elsewhere for a full eight months of the year.

And while we might be very familiar with their summertime habits, most of us know little about their lives once they leave. How do they get where they’re going? What do they eat, and what eats them? Where do they even spend the winters? (After all, “south” isn’t a very specific destination.)

There are as many answers to those questions as there are species of bird, and over the coming months I’ll talk about several of them. Today, I’ll focus on the Ruby-throated Hummingbird.

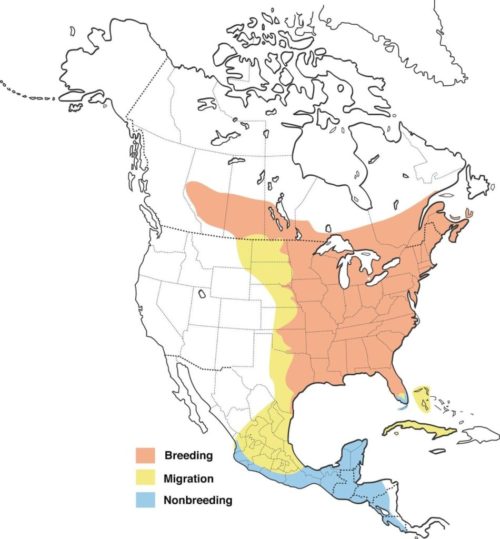

For those of us living in the Northeast (in fact, in virtually the entire eastern United States and Canada), “hummingbird” means just a single species: This little, shining-green, quicksilver bird whose male’s throat glitters a vivid red in the sunlight. That’s because the Ruby-throat is a true outlier: Among the more than 300 species that make up the vast hummingbird family Trochilidae, it’s the only one to brave our often harsh and unforgiving climate…even if for only part of the year.

As you travel south and west into warmer climes, the hummingbird picture is very different. Arizona, for example, has more than a dozen regularly occurring species, Mexico 50 or so, and Panama around 60. Hummingbird diversity reaches a breathtaking peak within a few degrees of the equator, with Colombia and Ecuador—two small countries split by that line—boasting nearly 150 species each.

Most of these species spend all or much of the year in one small area, but Ruby-throats don’t have that luxury. Like all hummingbirds, they rely on a diet of nectar and tiny insects and spiders, neither of which are in much supply during our long winter. To survive, therefore, they have to fly.

And fly they do. These minuscule birds—perhaps three inches long and weighing about a tenth of an ounce—undertake an extraordinary annual migration. Most spend their winters in Mexico and Central America as far south as Panama, a trip that usually includes a nonstop flight across the Gulf of Mexico. That flight—which can cover 1000 or more miles—can take 20 or more hours.

How remarkable is this feat? In a normal day, a Ruby-throat eats up to half its own body mass and drinks sixteen times that much. To expend so much energy without being able to replenish it makes their trip across the Gulf almost impossible to imagine.

As soon as they reach their destination, Ruby-throats’ habits change. Up here, for example, they’re birds of backyards and mixed fields and woodlands, but on their wintering grounds they choose landscapes as diverse as shade-grown coffee plantations, dry forests, and citrus groves.

None of their new homes provide for a relaxing winter vacation. On its nesting grounds, the Ruby-throat is usually the only bird that drinks nectar, but in Panama it joins those other 59 hummingbird species. Given how territorial most members of the family are, Ruby-throats must compete far more aggressively for a drink at a prized patch of flowers or feeder than they ever do up here.

During their months in Central America, Ruby-throats also must contend with myriad other threats. During the summer, their main predators are domestic cats, small, agile raptors (like Sharp-shinned Hawks and American Kestrels) and, remarkably, large insects like dragonflies and invasive Chinese Mantids. They face many of the same predators on their wintering grounds, but also must contend with wild cats like margays and jaguarundis, the small but fierce Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl (which often hunts by day), iguanas and other large lizards, and even toucans.

And then, after enduring all the challenges and risks of the winter months, they must retrace their same incredible journey as they head north with the changing seasons. When the first Ruby-throat visits our flowerbeds or feeder in May, we’re seeing a true survivor.

During the long, cold winter, it’s easy to forget that “our” migratory birds even exist, except as part of our yearning for spring to come. For me, though, there’s a true sense of wonder in getting a fuller picture of their lives, the lives that take place far from our backyards.

Next up when I return to this series: That bold, brash bully the Eastern Kingbird, whose winter story is one of my favorite of all.

Copyright © 2021 by Joseph Wallace

![broad-billed-hummingbird-melton Broad-billed hummingbird (male) in Arizona. [click image for more Arizona butterflies and photo credit.]](https://www.blog.sawmillriveraudubon.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/broad-billed-hummingbird-melton-1024x708-300x207.jpg)