Still Magical After All These Years

Like most of us, I loved watching fireflies as a child. During long summer evenings, those tiny flashing creatures were fairytale magic made real. And, like the wild blackberries we feasted on, the shrilling of the cicadas in the trees, and the Monarch caterpillars we found all over the milkweed near our house, they were a reassuring sign that fall—and school—were still far away and could be safely ignored.

But unlike most of us, I wasn’t satisfied with just watching fireflies for that brief stretch after dark before bedtime. I wanted the spectacle to last all night. So one evening when no one was looking, I smuggled a jarful of them into my bedroom and set the little insects free. Then I turned out the lights, hopped into bed, and waited for the light show to begin.

Fifteen minutes later, my mom came in to wish me good night. I will leave to the imagination her reaction to finding my walls covered in disgruntled—and resolutely unlit—fireflies. I stayed up much later than usual that night, but only until I caught every last one and released it safely back into the wild.

Even though I no longer want to bring fireflies indoors, I still find them as magical as I did as a child. And I’m thrilled when (as has happened this year) the woods and parks seem filled with them, countless individuals rising at dusk from the grass and gardens of my yard, neighbors’ lawns, and nearby parks.

This year’s show inspired me to spend some time learning about the odd little creatures that light up our midsummer evenings. As always seems to be the case with nature, what I’ve found out has been far more fascinating than I ever could have predicted.

First of all, there’s a lot more firefly diversity out there than I ever imagined. During my childhood summers on Cape Cod, I saw what I thought were two kinds: small black-and-pink ones that flashed a warm yellow (which I’ve discovered belong to the genus Photinus) and larger brownish ones with bright green flashes (Photuris). But it turns out that there may actually be as many as fifteen different species in the Northeast and more than 150 different across North America. Worldwide, scientists have identified at least 2000.

Not all firefly species light up. Among those that do, it works this way: The insects possess specialized organs in their abdomens (or sometimes elsewhere in their bodies) where a chemical (luciferin) and enzymes (luciferases) mix. When the mix is exposed to oxygen, it luminesces. The fireflies control their flashes by turning the oxygen supply on and off.

Most fireflies produce chemicals (called lucibufagins) that make them taste bitter to predators, and scientists think that their flashes originally evolved as a warning signal. Just as the red and orange coloration of Monarchs, Red Eft salamanders, and other species warns off predators during the day, fireflies have evolved a way to do the same at night.

But if firefly bioluminescence first evolved as a warning, it has since come to serve other purposes as well. For example, members of one genus of fireflies (the big, brownish Photuris I captured that childhood evening) use their lights as a lure, with a very different—and slightly ghoulish—goal in mind.

Photuris fireflies haven’t evolved the ability to make their own lucibufagins, the bitter-tasting toxins that protect most other species. As a result, in their natural state they taste good to birds, bats, and other predators.

So Photuris females have found a memorable way to protect themselves: They mimic the flashes of a female of a toxic genus, Photinus. When a male Photinus come swooping in, ready to mate, the female Photuris grabs and eats him instead. The predatory firefly then absorbs its victim’s toxic chemicals into her own blood, “borrowing” its bitter taste.

In luring the male Photinus to its doom, the predator is taking advantage of another use of bioluminescence: as a central part of fireflies’ mating rituals. In most species, the male flies a few feet above the ground and flashes. Females, who stay in the grass or on low bushes where all fireflies spend their days, watch the nearby males’ display, then flash back at their choice, who will then fly down to join them.

These courtship rites can be pretty complex. In some species, the male will flash a pattern of light from a specific height, and the female will wait a set amount of time before calling him in. In others, thousands of males in a single location will flash at the same time. This spectacular synchronized flashing (widely scattered species across the globe share this habit) has long fascinated both the general public and scientists, who are still not sure exactly how and why the fireflies accomplish this feat.

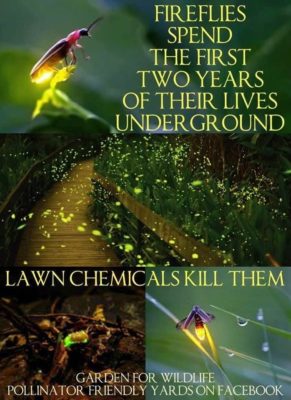

Inevitably, fireflies are threatened by what we humans are doing to our environment. Pesticides, habitat loss, and light pollution all take a toll. (How can a tiny insect outcompete the harsh glow of outdoor lights?) So, when you manage your property for birds, butterflies, and bees by planting pollinator gardens, letting your grass grow longer, and reducing or eliminating pesticide use, you’re also helping these vulnerable little creatures.

Why bother? For a myriad of reasons, including one that I think is both simple and vital: So today’s children, and those of generations to come, have the opportunity to experience the same magic I did when, all those years ago, I dreamed of a world lit by fireflies.

Copyright © 2022 by Joseph Wallace