The Prowler in the Backyard

My one and only encounter with a Bobcat took place many years ago and many miles away from my home in Westchester County, but it was such a vivid, unexpected experience that I know I’ll never forget it.

My wife and I were exploring Aransas National Wildlife Refuge (a sprawling reserve on the Texas Coast best known for the Whooping Cranes that winter there) when we saw two medium-sized mammals standing on the empty gravel road up ahead. At first glance, we thought that they were both White-tailed Deer, but a look through binoculars revealed something very different: A young White-tail buck facing off against a large, muscular Bobcat.

For minutes, the predator and its potential prey stood just a few feet apart, staring at each other. Then, finally, the Bobcat turned and—with the feline equivalent of a shrug—walked away without a backward glance. (And the buck? He was so filled with testosterone that when we drove up the road a few minutes later, he faced off against us, refusing to let us pass for several minutes!)

Ever since, my wife and I have hoped to see another Bobcat, just as many people we know have—including an increasing number here in Westchester. We haven’t yet…even though we’ve almost certainly walked past one of these medium-sized carnivores without realizing it. If you’ve gone for any long hikes in forested areas in recent years, you probably have, too.

It’s a wonderful fact that bobcats are thriving, both in New York’s forests and across much of the country. Researchers estimate that the total U.S. population is somewhere north of 3.5 million, an astonishing number for a predator in an increasingly built-up country. Even more encouragingly, Bobcats are still found in every state (as well as in southern Canada and northern Mexico), and numbers in most areas have been growing steadily since the 1990s.

There are a bunch of reasons why the Bobcat population is booming. Perhaps most importantly, until recent decades hunting them was not only legal, but encouraged: Some states even offered bounties for each one killed. Today, though the cats are still hunted or trapped in 38 states, seasons are carefully regulated and numbers kept under strict limits.

Just as importantly, Bobcats’ prey animals—including squirrels, rabbits, rats, and mice—are plentiful almost everywhere. All those creatures do very well in the kinds of environments humans create, including patches of forest, farmland, and larger wooded parks, which in turn attracts the stealthy animals that hunt them.

With so many Bobcats roaming around out there, it’s no wonder that sightings have increased greatly in suburban counties like Westchester. Yet even now, glimpsing one remains a thrilling surprise, because this is one animal that prefers to stay hidden. And when a Bobcat doesn’t want to be seen, it isn’t.

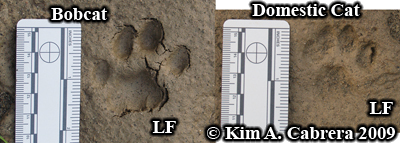

Even when you don’t spot one, though, you might come across other—very catlike!—signs that reveal the animals’ presence. For example, just as domestic cats do in a litter pan, Bobcats cover their scat with leaves, dirt, or snow. So if you find a fresh mound in your yard or beside a trail, usually with claw marks in the soil around it, you didn’t miss seeing a Bobcat by much.

These mounds, as well as scratches on the bark of tree trunks, serve as calling cards for Bobcats marking their territory. Like many other mammals, they rely on both scent and sight to announce, “I am here!” to potential competitors. Like domestic tomcats, the male cats also spray, leaving such a pungent odor that even humans can detect the calling card.

Another way that Bobcats mark their territories: By unleashing their guttural, haunting screams across the forest night. (I once heard one calling while staying in a lonely cabin in an untracked Vermont forest, and didn’t get much sleep for the rest of the night.

Bobcat Calls

Bobcats can be especially noisy during breeding season, which starts in midwinter and can last for several months. If you happen to see two Bobcats chasing, ambushing, or wrestling with each other (more catlike behavior), you’re probably witnessing a courting pair.

The cats’ preferred habitats include rocky slopes, rockpiles, ledges, and caves, all of which offer safety and the ability to see without being seen. These areas are especially prized during breeding season, when a female will build a warm, dry, and hard-to-find den amid the rocks or in a cave.

Here she will give birth to between one and five young. Like all cats, Bobcat kittens are born blind and helpless, completely dependent first on their mother’s milk and later on the meat she brings back from her hunts.

Finally, after about two months, the kittens will emerge from the den to begin the next stage of their education. Before then, though, their mother will have built several other dens in the vicinity. Once the young cats are out and about, these dens will help protect them from Coyotes, Golden Eagles, Great Horned Owls, and other powerful predators.

Like every creature in the world we humans have made, Bobcat populations still face some threats. Overdevelopment can drive away even this adaptable species. Collisions with vehicles take a toll, and diseases such as rabies, mange, and distemper, frequently spread by domestic animals, can also suppress Bobcat populations. But for now, the species is on an upward trajectory nearly all across its range.

As for my wife and me, we still haven’t seen a Bobcat since our encounter in Texas all those years ago. Even so, whenever we’re out walking in the woods, we hope to see a tawny form slipping away in the gloom…or even stopping to look back at us with golden eyes. Someday, we’re sure, we’ll have another encounter with the prowler in our backyard.

Copyright © 2023 by Joseph Wallace