Still Being Rescued

As long as I can remember, I’ve had two great enthusiasms in my life: writing and nature, especially birds.

People talk about the “spark bird,” the one species—the one sighting—that inspires a lifetime passion. I guess if I had to choose one, it would be the gawky, dinosaur-like Glossy Ibis, which I saw at a very young age when my Dad took me to Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge.

But in truth I was that, even though I was a city kid, I was sparked by all birds, and all the natural world around me. My family’s single-family house in Midwood, Brooklyn, wasn’t exactly located out in the wilds, but it did boast small yards in the front and back, flowering lilacs and rhododendrons, and a towering magnolia tree I’d climb when I wanted to be alone.

And that was all I needed. Together, those small squares of green served to set the imagination of this nature-mad kid afire. They were my Amazon, my Congo, my doorways to adventure and discovery. (Even if my “discoveries” usually amounted to weird grubs, goggle-eyed mantises, and the occasional aggressive bee.)

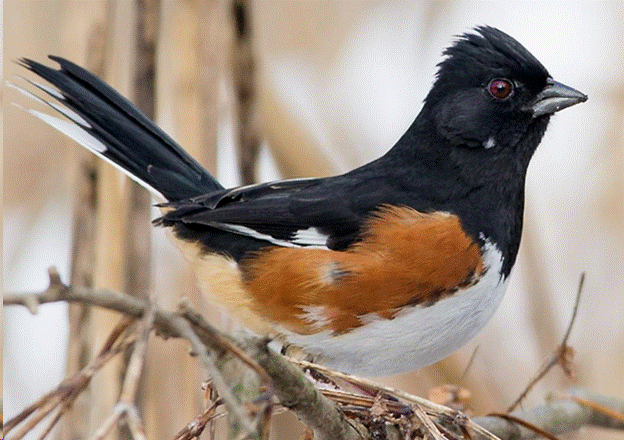

And there were birds to see there, too, whose beauty and freedom both entranced me. One spring, I hung a tinfoil bird feeder from a low branch on the magnolia. Then, after school each day, I watched out the back window as it attracted not only seed-eating sparrows and finches but more unexpected species like gaudy Baltimore Orioles, dapper Black-throated Blue Warblers, and Eastern Towhees (though they were called “Rufous-sided” back then). None of these species visited the feeder, but all seemed to recognize that they were safe to rest and forage in our yard before continuing their journeys.

That spring gave me my first glimpse of the vast, unseen river of birds, millions upon millions strong, that passed high overhead during migration nights. I felt awestruck that my little yard was even a tiny island in that river.

I also wanted desperately to join the river myself. As a child I couldn’t do that, of course, couldn’t escape my familiar little neighborhood and explore the great world beyond. So instead I turned to writing, where I could create my own worlds and travel as far as I wanted without leaving my house. When I wasn’t digging for grubs or watching birds, I was upstairs in my room hammering away at my typewriter, writing adventure and science fiction and mystery stories, creating all the worlds I was so eager to visit.

Until I went to college and just…stopped.

Looking back, I can see some reasons why: Over the previous years, my father had suffered from repeated bouts of ill health (two heart attacks, a cancer scare, a mysterious blood disorder) that had brought him near to death more than once. Understandably, my mother, my brothers, and I had struggled under the continuing burdens of fear and uncertainty. It was hard to be creative when the real world around me seemed so all-consuming.

And then, during my sophomore year in college, my parents sold our house in Midwood and moved to a brownstone in Brooklyn Heights. Though I was happy for them (they adored Manhattan and wanted to be closer to it), the move left me feeling adrift, cut off from things I relied on, like my neighborhood friends and my favorite pizza place and candy shop.

And, most of all, I felt cut off from nature. Unlike our old house, the brownstone had no front yard and only big concrete deck in the courtyard out back. Sure, there were trees in the courtyard, but none were accessible. They could never be my rainforest, never beckon to migrating birds the way my old backyard had, never inspire me to dream of the big world out there.

Cut off from all that, I stopped writing. For at least two years, I didn’t put a word down on the page that wasn’t part of an assignment. Nor did I look at a single bird or even pay any attention to the world outside my head, except maybe to check the weather.

And yet, even as I had abandoned both writing and nature, I still didn’t recognize the crucial connection between these two foundations that my life had been built on. And I might never have discovered them—much less figured out how to break through what had been blocking me—if my friend Tom hadn’t invited me to spend the summer after junior year in his family’s tiny cabin in the Vermont wilderness.

Tom had gotten a grant to research his senior Sociology project, and he said he’d welcome company in the cabin. “You’re always saying that you want to write,” he pointed out. “So stop talking about it, come up there, and write!”

I often wonder where my future would have gone if I’d turned down his offer, chosen to spend the summer working a minimum-wage job in NYC and sleeping on the saggy single bed in my parents’ laundry room. (There was no extra bedroom for me in the brownstone.) But while I’ve made plenty of bad decisions in my life, I didn’t this time: I accepted Tom’s offer like a drowning man clutching at a lifebuoy.

As the school year came to an end, I withdrew the last of the savings I’d hoarded from my job the previous summer, threw some clothes in a duffel bag, and grabbed my old pair of 7×35 binocs and my Peterson field guide. And then Tom and I headed north.

The one-room cabin had no electricity, no heat, no plumbing, only Coleman lanterns for light, a woodstove for heat, and a tiny stovetop powered by Coleman fuel as well. The bathroom was an outhouse or the great outdoors, while for freshwater we hiked with jugs to a well half a mile away. Our second day there, my watch ran down, and I never wound it again that summer. Why bother? We lived by the sun and the weather.

It was heaven. Every day, spiral notebook on my lap and ballpoint pen in hand (no electricity for my typewriter!), I’d sit by an open window that looked out over the greenest world I’d ever seen, and write and write and write. I worked on a thriller set in Uganda (a country I’d visited, and barely escaped from, five years earlier), and the words just poured out onto the page. It was as if all the fears and dislocations of recent years had built an unseen dam somewhere inside me, and the dam had finally been breached. The river could flow clear again.

What breached that dam? Time and peace did…but most of all it was the world outside the window, the one Tom and I got to explore when we put down our books.

We canoed and fished in nearby Lake Ninevah, hiked along rushing Patch Brook, met a mother porcupine and her soft-spined new baby in a young aspen tree, camped amid fields of blueberries on the slopes of undeveloped Saltash Mountain, woke in our sleeping bags to the yipping of coywolves and the bone-chilling shrieks of a bobcat.

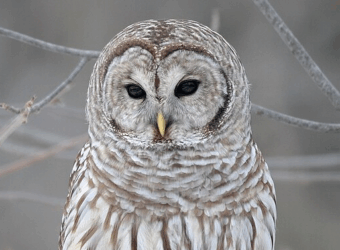

And the birds. The birds! I remember so vividly the soundtrack of that summer, and it wasn’t Debbie Boone’s “You Light Up My Life” or other top chart hits of the time. It was the “Tea-cher Tea-cher Tea-CHER!” of the Ovenbirds that nested throughout the woods; the “Old Sam Peabody Peabody Peabody” of the White-throated Sparrows; the loud, unsettling “Who Cooks for You? Who Cooks for You-allllll!!” of the Barred Owls that resounded through the woods on moonlit nights; the haunting strains of the Hermit Thrush’s ethereal song wafting down from Saltash’s forested slopes; and so many more.

I didn’t finish my Uganda novel until long after summer ended, and never saw it published. Nor did I spot any especially rare birds during those weeks. But you know what? None of that mattered. What mattered was that I wrote, living inside my story day after day while the natural world all around filled me to the brim and beyond. Together, writing and nature made me into more than the sum of my parts. They made me whole again.

It’s not claiming too much to say that by showing me that I needed both the world inside and the world outside to create, breathe, live, those weeks in Vermont rescued me. Or that, as I sit here right now, writing this while I listen to the sound of birdsong just outside my window, they are still rescuing me today.

Copyright © 2025 by Joseph Wallace