Doorway to a Better World

As a nature writer, I’ve spent much of my life traveling the U.S. and beyond. Almost always, my goal has been to visit the world’s remaining untouched forests, deserts, and mountains, and then tell others about what survives there, the threats they face, and our critical responsibility to preserve what’s left.

It’s been a fulfilling and fortunate career. And it all began with a tinfoil baking pan!

The spring I turned fifteen, I decided that I wanted to set up a bird feeder in our postage-stamp backyard in Midwood, Brooklyn. I can’t quite recall where I got the idea, but my family couldn’t have been surprised. I’d been mad about nature since I was little, always pushing my parents to take me to the American Museum of Natural History or the Bronx Zoo and reading every book I could find on exotic travel and adventure.

But this was different than books or museums. This was real.

Almost immediately, I hit my first roadblock: We didn’t own a birdfeeder, and I was too broke to buy one. An intensive hunt through the house for a good substitute (my mom’s jewelry box? perhaps not) eventually turned up a solution: One of the 9×13 tinfoil pans I found in a kitchen cabinet.

I don’t remember asking permission to take it. I imagine I realized, correctly, that by the time I’d punched holes in its sides, strung it with rope, hung it from the magnolia tree in our yard, and filled it with birdseed, no one would want to serve a pot roast in it.

I have to admit that I didn’t expect it to attract much beyond pigeons, starlings, House Sparrows—typical city birds. After all, our backyard was not only tiny but placed right in the middle of one of the biggest cities on earth. Even if migrating birds did fly overhead, how on earth were they ever going to spot one little tinfoil pan far below?

For the first few days, it seemed like I’d been right to keep my expectations low. The feeder was deserted when I headed off to school and untouched when I got home in the afternoon. I decided that I might as well have dug a pit in the lawn to try to catch a tiger.

Then one day I gave a cursory glance out the back window and saw two hefty Mourning Doves lounging comfortably in the feeder as they dined. (This dove habit forced me to repeatedly push the dented bottom of the pan back into shape.) Next came a small flock of White-throated Sparrows eating the seed the doves had scattered on the grass, and soon cardinals, juncos, Song Sparrows, and others were also regular visitors.

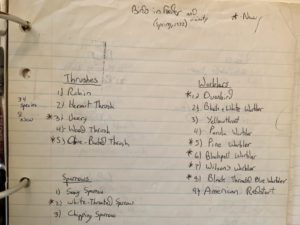

But what most amazed me then—and still astounds me today—was how many insect-eating birds visited our yard that spring without even going near the feeder. My final list included nine species of warblers (including Black-throated Blue, Parula, and Wilson’s), Hermit, Wood, and Olive-backed (now known as Swainson’s) Thrushes, Brown Thrasher, Rufous-sided Towhee, and several others.

It seemed miraculous that these birds, looking down as they flew over, had spotted the birds gathered at the feeder. And then, knowing it was a safe place to rest and search for insects to eat, they chose to descend—into my yard!—and stay a few hours or overnight before heading north once again.

Far more than any book, TV show, or museum, my encounters with those tiny travelers taught me an enduring lesson about the world: That everything in it is connected. Looking out my back window, I understood for the first time that a vast river of birds flows across our skies every spring and fall. It’s made up of billions of birds that depend on oases along the way to survive, oases as small as a patch of green in the midst of a giant urban sprawl.

I learned something else that spring. I understood that I had a role to play in making sure that river always flowed. I had to share what I’d learned, to work to preserve not only those fragile, precious migrating birds, but their whole vulnerable world that existed far beyond my backyard.

I’d been wondering why my memories of that long-ago spring have returned so vividly in recent months, and I think I’ve figured it out: Because in recent years feeding the birds has become an increasingly controversial topic.

Perhaps inevitably, the anti-feeder voices have risen in response to a surge in enthusiasm for birdfeeders, and birds overall, in the wake of pandemic lockdowns. Seeking something new to focus on while stuck at home, millions of people across the world set up feeders and started paying attention to what showed up there.

The objections take a variety of shapes. Some people worry that feeders won’t be kept clean, which can actually spread disease among visiting birds. (Click here for instructions on how to keep your feeder safe for them.) But other objections are on more philosophical grounds, based on the principle that “we need to let nature fend for itself” and stop “interfering.”

I understand stand such feelings, but I’m sure it’s clear that I take a more nuanced view. A feeder that supports little more than those invasive pests, House Sparrows, is doing more harm than good. But I believe that a carefully maintained winter feeder stocked with seeds that will attract native songbirds (like safflower, appealing to native species but not to most invasive ones) may be crucial to the future of the planet.

Crucial? How can that be? I think the answer comes from my own experience, my belief that feeders can open the same door to nature for today’s young people—actually, people of any age—that they opened for me. In fact, I believe they have to. I have a loud voice, but however much I write, talk, or agitate, endangered habitats and their inhabitant will never survive unless countless others connect with the wider world around them, just as I did decades ago.

My communities today (both live and online) are filled with people who already understand what needs to be done to protect both local birds and the world’s dwindling wild places. We must plant native gardens to attract pollinators, join—or start—groups to work with and lobby local officials, give financial support to organizations that do the same on an international scale, and so much more.

But our knowledge and commitment had to come from somewhere, and that is just as true in our increasingly urbanized world today. What about those who don’t yet understand the challenges ahead? Who don’t have spacious yards to fill with pollinator plants? Who aren’t fortunate enough to have the funds to support environmental organizations, or the time and access to learn more about what needs to be done?

Finding new ways to overcome these challenges, to educate and involve those who may be hard to reach, is essential. In the meantime, though, there’s one thing most people already do have: A windowsill or a nearby patch of green—however small—where they can place a birdfeeder…and then watch some of nature’s wonders come to them. This simple interaction might just spur them to fight the important battles to come, as it did for me.

And if they don’t happen to have a feeder? No problem at all. Any old tinfoil tray—or a plastic bottle!—will do.

By Joseph Wallace

Copyright © 2022