Three Conversations About One Thing

I had a wonderful walk at Rockefeller State Park a couple of weeks ago, one I’m still thinking about all this time later.

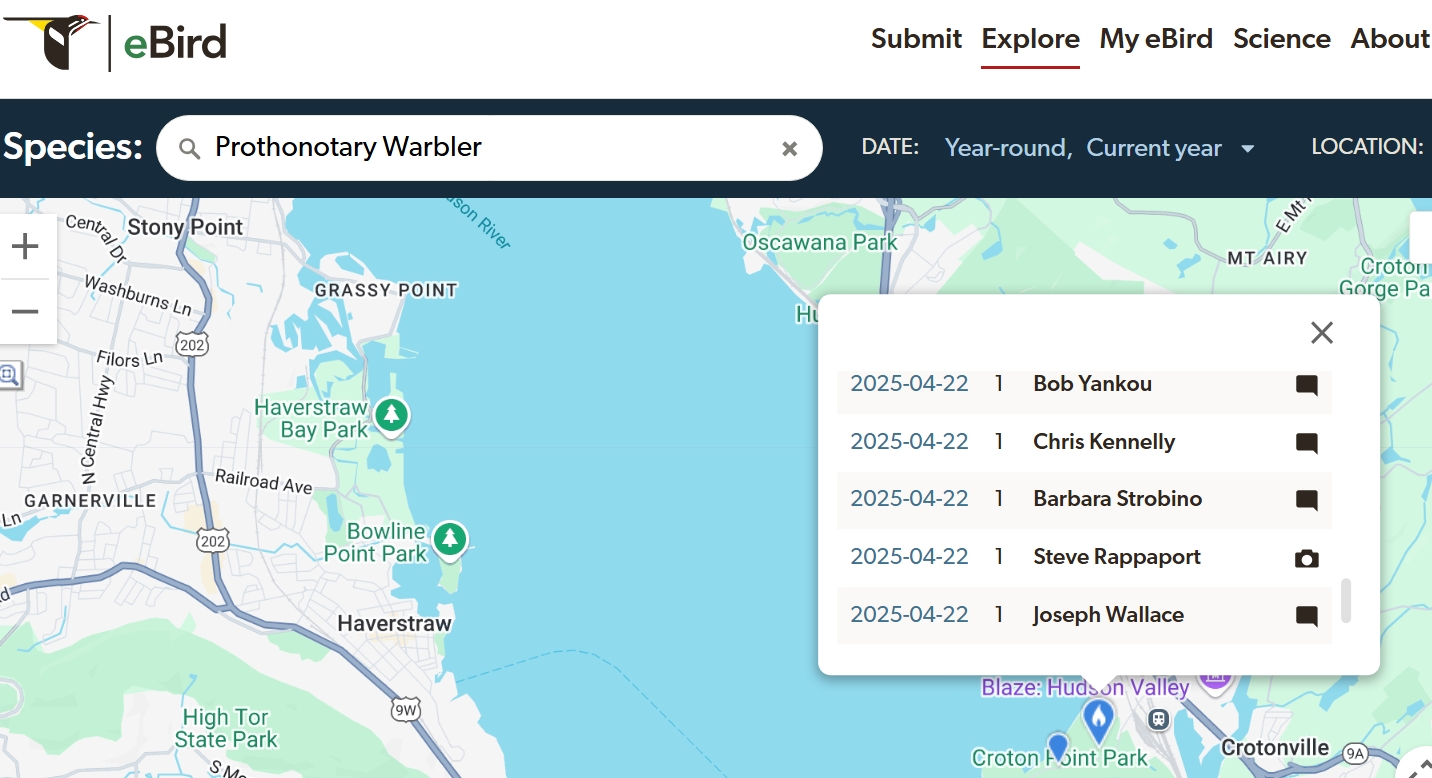

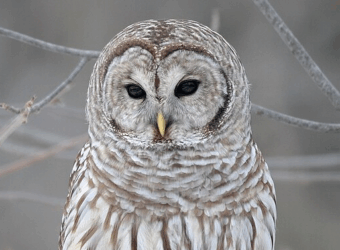

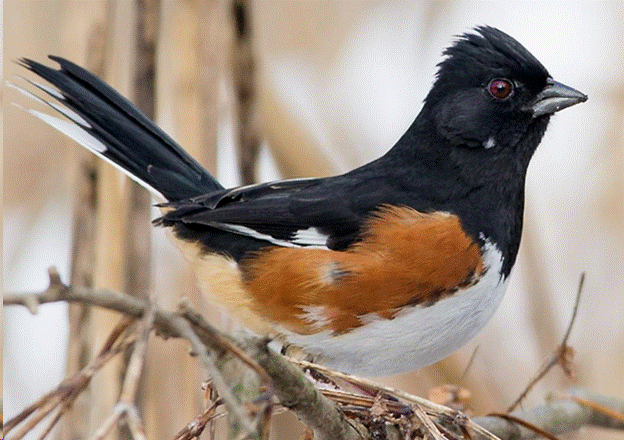

I saw a whole bunch of great birds. Of course I did! It was migration season, when the park is filled with them. Among the avian treats I came upon were warblers, including a dapper Chestnut-sided and a wide-eyed Ovenbird bobbing along the forest floor. Also vireos, woodpeckers, thrushes (including the rarely seen Gray-cheeked), and many others. (If you’re interested, here’s my complete list from that day: https://ebird.org/checklist/S275829450 .)

However satisfying the birding was, though, it wasn’t these sightings that made my walk so memorable. It was the people I encountered along the way.

Almost every time I go out with my binoculars, people stop to ask me what I’m looking at. I always try to give them a real answer, since I believe that we birders—and all people who care about nature—owe a friendly, open reply to anyone interested enough to ask. It’s one small way we can help get more people more engaged.

On this day, I was approached three times. Each time, I was asked a different question, but as the day went on I realized that the people I met all wanted the same thing: To truly understand.

My first encounter was with a couple in their fifties. “What are you looking for?” the man asked.

“It’s funny,” I said. “I’m not actually looking for anything. I’m just hoping that some of the birds here let me see them.”

“They don’t always, do they?” the woman asked.

“Oh, no! Sometimes it seems hardly ever.” I smiled at them. “But regardless of what I see, searching is my favorite part.”

“It is?” she said.

I nodded. “To me, birding is like an endless treasure hunt,” I explained. “I never know what I might see, but I know it could be something special, something I’ve never seen before. I’m always hopeful.”

I could see that they were getting it. “A treasure hunt,” the woman said, nodding. “Yes.”

I made to walk on, but then the man said suddenly, “Have you ever seen a Scarlet Tanager?”

“Sure,” I said. “They nest here, and some are migrating through right now.”

“I spotted one in our backyard a few years ago,” he said. “I thought it was the most beautiful thing I’d ever seen.”

“Keep your eyes out!” I told him. “But you should know that if you do spot one today, it’s going to look very different.”

I pulled out my phone and found a photo of a male Scarlet Tanager in non-breeding plumage. “Wow,” he said. “It should be called the Green-and-Black Tanager.”

Next was a pair of young women who’d been jogging. They walked past me, then stopped and looked back. “Are you birdwatching?” one asked.

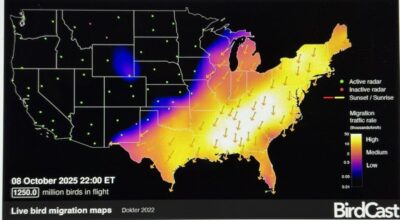

I said yes and admitted that there wasn’t much to see at the moment. They shrugged and started to turn away, but then I found myself saying, “I find it incredible, though, that some of the birds I’ve seen here today weigh less than an ounce…but in a few days they’ll be flying thousands of miles to reach their wintering grounds.”

That got their attention. “Thousands of miles?” one said.

“Yup.” I paused. “I read that the Blackpoll Warbler, for instance, can fly 2000 miles over the ocean without stopping once.”

“Two thousand miles!” the woman said, shaking her head. “That’s amazing.”

Then she frowned. “How about the hummingbirds I see in my garden? Do those teeny things migrate, too?”

“They sure do,” I said.

Still frowning, she looked down at the water bottle in her hand and then up at the sky. “But how do they stay hydrated up there?”

I’d never asked myself that question, so I could only turn my palms up.

“Maybe…” She thought about it. “Maybe they get all the water they need when they fly through the clouds.”

I loved that idea. “Maybe they do.”

For a long moment we all stood there, imagining those minuscule birds flying thousands of miles, drinking from the clouds. Then the second woman, who’d stayed quiet throughout our little conversation, shook her head.

“Little miracles, that’s what they are,” she said

And then there was a couple in their thirties. I’d walked past them earlier, and something about them had stayed in my mind. Maybe it was the obvious pleasure they were taking in each other’s company, or the intensity of their conversation.

Whatever it was, they looked like people who had enough to talk about without paying any attention to me. So when our eyes me I just smiled and said, “Hello again!” as I passed.

So I was surprised when they stopped. “What have you seen since we last crossed paths?” the woman asked.

Again, I didn’t mention specific birds. Instead, I said, “During spring and fall migration—”

Then I hesitated for a moment. Searching again for the words, I discovered an unexpected catch in my throat. “It’s just an amazing thing,” I managed to say, “that there’s, like, this enormous ebb and flow of life, this huge tide taking place everywhere on earth.” I took a deep breath. “On these walks, I feel…awed to get tiny glimpses of the tide right here.”

I forced myself not to look away in embarrassment. Who was this guy getting emotional about birds in front of complete strangers? And the couple were staring at me with wide eyes. But then the man nodded as if he understood exactly what I was talking about. “It’s like fishing,” he said.

I must have looked puzzled, because he explained. “You’re looking down at the surface of the water,” he said, “and as far as you can tell there’s nothing there. You can only imagine everything that’s going on below the surface, not see it. So the whole thing feels like a kind of fantasy.”

He paused, spreading his hands as if over a vast, opaque surface. “But then something changes,” he said. “The tide? Temperature? You never know exactly what. But something changes, and suddenly your imagination becomes real, the fish rise, and you understand your place in it all.”

The woman was smiling at both of us. “Suddenly you connect,” she said, putting into words what I’d been feeling all day.

After that, we stood for a few moments, only the sound of the breeze in the leaves and the calls of distant birds breaking the silence. We’d said all we needed to, so moment later, with warm goodbyes, we parted ways.

Looking back, I know I was lucky that day at Rockefeller. Lucky to get a sense of the vast tide of life that surrounds us. And luckier still, I think, to encounter these six people who felt comfortable enough to engage with a tall, gawky, binocular-clad stranger. And, when he answered their questions, to understand and express their own feelings about a park—and a world—we all shared.

Like the young jogger said: Little miracles. Start to finish, it was a day filled with them.

Copyright © 2025 by Joseph Wallace